The research activities which led to the production of this work were made possible by a research grant awarded to the author by the Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences Research Committee of the University of Benin in April 1976 (cf. FASS. 12/76/77). A subsequent supplementary grant from the committee in 1978 served to support the project to its completion. I wish to express my deep appreciation for the opportunity provided to me by this support to make this little contribution to the development and study of Ẹdo.

In a work such as this, it is inevitable that assistance is sought and received from diverse quarters. Throughout this project, numerous people in Benin City and elsewhere gave of their time, expertise, and knowledge to make possible its completion. It is certainly impossible for me to acknowledge individually everyone of these people, but to each of them, I express my sincere gratitude and indebtedness for their help.

I must, however, acknowledge with thanks, the special assistance received from certain individuals and institutions. First among these are my various Research Assistants, in particular, Mr. Pius Guobadia, who worked diligently on a full-time basis throughout the first phase of the project. Others, who must be specially mentioned are Ọsayaba Agheyisi, Nogieru Agbọnkọnkọn and Roland Ugiagbe Aigbe who worked with me, part-time, at different periods.

Mr. G.N.I. Enobakhare read portions of the draft and made useful comments and contributions from which this work has benefited.

Professor William Welmers gave generously of his books on Ẹdo and other reference materials, which turned out to be very useful for aspects of the project. Also Mr. Ikponwonsa Ọsẹmwengie made available to me his personal copy of Melzian’s Dictionary.

My special thanks also go to the Radio Bendel authorities for making available to me several tapes of their Ẹdo Language programmes.

The Departments of Linguistics of both the University of Kansas,

Finally, I wish to express my sincere thanks to the Junior Staff members of the Department of Linguistics and African Languages, University of Benin, for their individual and collective support throughout the project, and most especially to Mr. Simon Odibo, who undertook most diligently, the onerous task of typing the various drafts of the manuscript.

In a work such as this, there are bound to be a number of inadequacies and shortcomings. For every one of them, I accept full responsibility.

January, 1982

R.N. Agheyisi

Any formal account on any aspect of Ẹdo language must begin with

a clarification of the term

|

|

| Egharevba 1954:8) |

The other names also currently associated with the city and the language

of its inhabitants, namely,

|

|

| Egharevba 1956:3) |

|

|

| (Egharevba 1954:8) |

Further ambiguity was introduced later into the reference of the term

However, the ultimate solution to the nomenclatural problem may be

found in the recent proposal by Elugbe (1979) of the designation

The focus of the present work being on the single language per se,

rather than the group of related languages, the usual nomenclatural ambiguity

is presumed to be irrelevant, and so

The Ẹdo language is today spoken natively throughout most of the

territory coterminous with the Benin Division of the former Mid-Western

State of Nigeria, and which has now been demarcated into the Orẹdo, Ovia

and Orhionmwọn Local Government Areas. This same area constituted the

permanent core of the pre-colonial Benin Kingdom and empire and its

inhabitants have always referred to themselves as Ivbi-Ẹdo. The estimated

area of the territory is about 10,372 square kilometres, while the 1952 and

1963 population figures for the Division are given as 292,081 and 429,907

respectively. A small proportion of the population however constitutes the

non-Ẹdo immigrants who are either permanent or temporary residents in

the area. On the other hand, there are believed to be other communities of

Ẹdo native speakers in the Okitipupa Division of Ondo Province, as well as

in and around Akure in Ondo State. In addition to these native speakers,

thousands of other residents in the Bendel State speak Ẹdo as a second

language, especially those with Ishan and Afenmai native language back-

The main Ẹdo speech community is generally homogeneous, though

noticeable peculiarities do exist in the speech of the inhabitants of some of

the peripheral communities. For example the common saying about Oza

speech:

Investigations into the nature of the historical relationship between

the various Nigerian languages are still at a very elementary stage. Only very

broad outlines of the pattern of genetic relationship have yet emerged. It is

now a firmly established fact that Ẹdo is a core member of a larger group

of genetically related languages and dialect clusters, usually referred to as

the Ẹdoid Group of languages, which in turn belongs, along with other Nigerian

languages such as Yoruba, Nupe, Idoma, Igbo, and Izon, to the KWA branch

of the NIGER — CONGO family (Westermann 1952; Greenberg 1966).

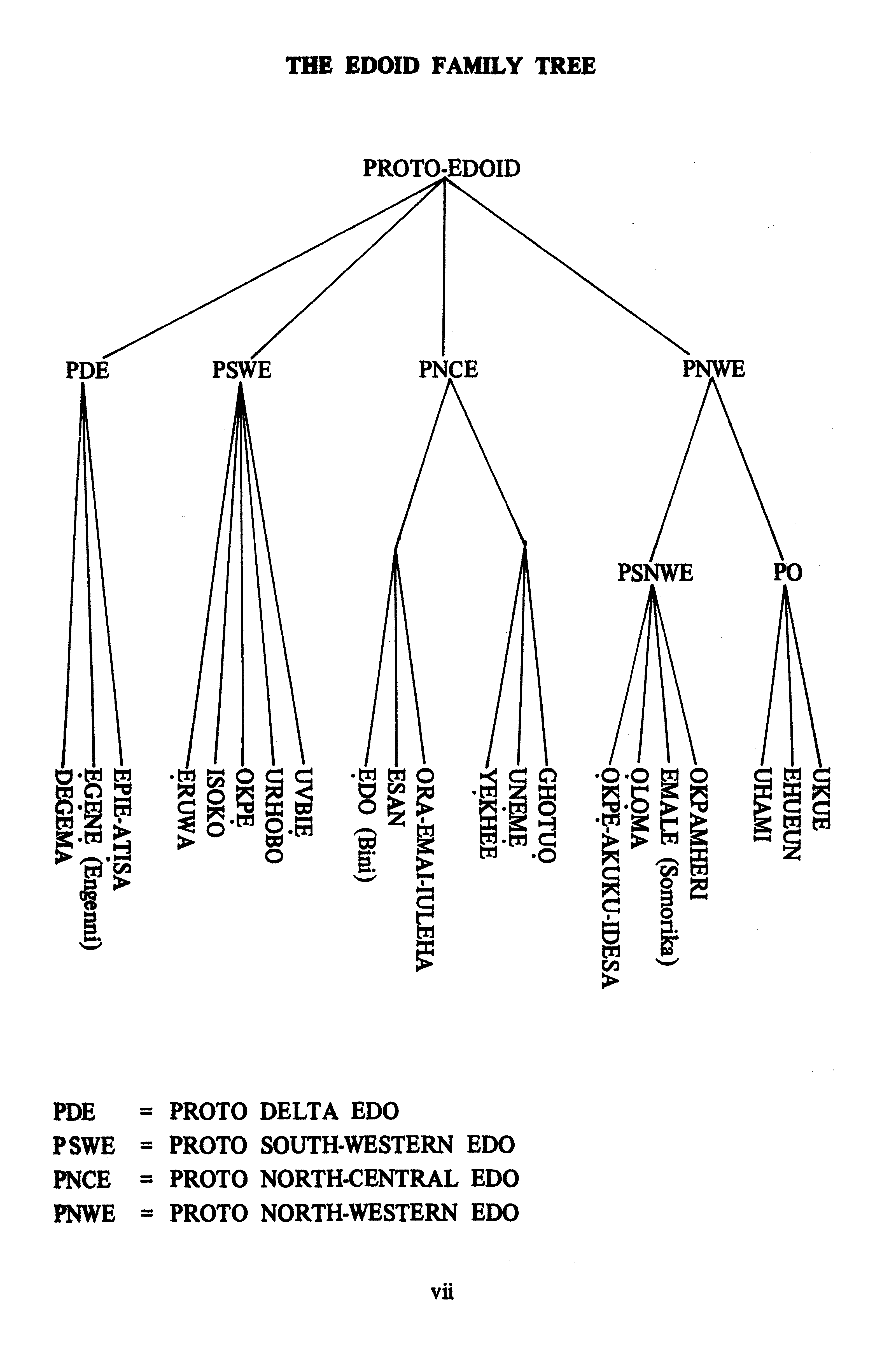

Further research into the structure of relationship within the Ẹdoid

Group has led to more detailed sub-grouping of the languages. For example

the classification presented below is the latest rendering of the relationship

by Elugbe in his 1979 paper. It presumably supercedes other earlier analyses

of the relationship such as Elugbe 1973; Hoffmann 1974; etc.

There is no doubt that it would be most desirable to be able to complement,

and indeed confirm, some of the sketchy and sometimes undocumented accounts from oral traditions about the cultural heritage of the

various linguistic groups, with inferences derivable from language classifications such as these. For example, many of the communities within and

without Bendel State, in their oral traditions, trace their origins to Benin

City or other parts of the Benin Kingdom. (Moore: 1970; Bosah 1976; Obuke

1975; etc.). To what extent are these accounts of migrations reconcilable

with the diversification in speech forms implied in the classifications? Unfortunately

the present classifications are yet too limited in the information

they provide. Until it becomes possible to estimate the dates of the various

sub-groupings the historical primacy of any one of them cannot be established.

The present study, in many respects, builds on the foundation of previous lexicographical works on Ẹdo such as Thomas’ Anthropological Report on the Ẹdo-Speaking Peoples; Munro’s English-Ẹdo Wordlist, and most importantly, Hans Melzian’s most commendable earlier work on Ẹdo Language; in particular, his A concise Dictionary of the Bini Language of Southern Nigeria (1937), which unfortunately has long gone out of print. The few copies of this work which today exist are confined to the private collections of a few privileged individuals, and some institutional libraries mainly in Britain and America. This has, in general, rendered this work inaccessible to the interested man-in-the-street, especially in the Ẹdo linguistic community, where it is probably most relevant. Furthermore, the absence of any other comprehensive lexicographical publication on Ẹdo since Melzian’s has helped to create the undesirable vacuum that has since existed in this aspect of available reference material on the Language. The need to fill this vacuum has been a prime motivation for the undertaking of this work.

This dictionary is designed basically to reflect Ẹdo contemporary usage,

with particular awareness of the complex sociolinguistic environment in

which the language is being used today. In this respect, it anticipates the

special needs of the average Ẹdo speaker, for whom the necessity to be able

to operate bilingually in Ẹdo and English has become a pressing reality. This

perspective is clearly reflected in both the selection of entries for the dictionary,

as well as the quality and range of information provided for each

entry. Thus, there are, for example, a number of entries found in Melzian’s

dictionary, deriving particularly from his intensive research into Ẹdo traditional

and religious rituals and folklife, which are not found in the present

work; while on the other hand, there is a sizeable number of everyday

vocabulary and adapted loan words included here, which are not found in

the earlier work. Generally, however, the underlying objective, which has

been to produce from the available resources on Ẹdo, a collection which

would qualify for the designation

Special efforts have also been made to incorporate both phonological

and grammatical information for each of the entries, in anticipation of the

specialized needs of the language researcher and others interested in linguistic

The research activities which led to the production of this work were initiated in 1976, and carried out in three phases. Work in the first phase focussed around the compilation of Ẹdo words from miscellaneous sources, including published works, manuscripts, recorded tapes and individual contacts. The list of the formal works consulted is provided at the end of the section.

The main activity of this phase entailed combing through these various sources for words and expressions to be used as entries in the dictionary. Melzian’s Dictionary served as a final reference in this regard, especially for crosschecking for additional items that may have been overlooked or unattested in the other sources. Also most of the Latin names for plants and trees were taken directly from this dictionary.

This phase of the project did not end until mid 1979, when the target of 7,500 items was eventually achieved. It was expected that after analysis of the data thus collected, at least half of the items would be selected as suitable entries.

The second phase was devoted to the grammatical and semantic analysis

of the data that had been assembled. The objective was to determine the

lexical status of each item as well as their grammatical and semantic properties.

As a result of work in this phase, the 7,500 items compiled previously

became analyzed into a little under four thousand entries. This reduction

in number of entries came about mainly by the application of the principle

whereby forms which are grammatically predictable (i.e. forms derivable from

others by highly productive grammatical rules) did not qualify as independent

entries. Thus, for example, the set of adjectives derivable from ideophonic

adverbs by the addition of né- as prefix, such as: nemosemose

The final phase of the project was devoted to processing and collating all the information that had been assembled on the various entries, and in particular, to conducting a final cross-checking of the meanings of various words. It was often necessary to hold discussion and consultation sessions with various individuals over the meanings of certain items. In the final draft that emerged from this phase, for each entry in the dictionary, the following categories of information were provided:

| (1) | a phonetic transcription, with tone indicated; |

| (2) | the grammatical category to which the word belongs; and |

| (3) | the meaning of the word in English, often with illustration of usage in Ẹdo. |

| Aigbe, Emman I. | 1960. | Iyeva yan Ariasẹn vbe Itan Ẹdo. Lagos |

| Ebọhon, Ọsẹmwegie |

Ọba Ehẹngbuda Kevbe Agbọn-Izẹlọghọmwan. Ethiope Publishing Corporation, Benin City. | |

| Egharevba, Jacob U. | Ekherhe vbe Itan Ẹdo. Benin City. | |

| Okha Ẹdo. Benin City. | ||

| 1972. |

Itan Edagbon mwen. Ethiope Publishing Corporation, Benin City. | |

| Iha Ominigbọn. Benin City. | ||

| Agbẹdogbẹyo. Benin City. | ||

| Ebe Imina. Benin City. | ||

| Idahosa, U.A. |

Eb’ omunhẹn N’ogieva, Primer Two. Longmans, Green & Co., Ibadan. | |

| Melzian, Hans |

1937. |

A concise Dictionary of the Bini Language of Southern Nigeria. London. |

| Munro, D.A. |

English — Edo wordlist. Institute of African Studies, U.I. Occasional Publications No. 7. | |

| Thomas, N.W. |

1910. |

Anthropological Report on the Ẹdo-speaking Peoples. 2 Vols. London. |

| as | ada | |

||

| as | ebe | |

||

| as | ẹdẹ | |

||

| as | iri | |

||

| as | okò | |

||

| as | ọgọ́ | |

||

| as | uguu | |

||

| as | ọdan | |

||

| as | ọdẹn | |

||

| as | ivin | |

||

| as | edọn | |

||

| as | ẹdun | |

| as | in | baa | |

|

| as | in | dẹ | |

|

| as | in | faa | |

|

| as | in | ga | |

|

| as | in | gba | |

|

| as | in | ghee | |

|

| as | in | he | |

|

| as | in | kaa | |

|

| as | in | khọ | |

|

| as | in | kpaa | |

|

| as | in | laọ | |

|

| as | in | maa | |

|

| as | in | mwẹn | |

|

| as | in | na | |

|

| as | in | pẹpẹ | |

|

| as | in | re | |

|

| as | in | rhie | |

|

| as | in | rre | |

|

| as | in | saa | |

|

| as | in | taa | |

|

| as | in | vaa | |

|

| as | in | vbaa | |

|

| as | in | wii | |

|

| as | in | yee | |

|

| as | in | zọọ | |

Also consistent with the stipulations of the official orthography, tone

marking has been confined exclusively to those forms which might remain

ambiguous without the indication of tone. The tone marks on such forms

are expected therefore to be regarded as part of their regular spelling. In

Parts of speech labels which have been employed in the categorization of Ẹdo words in this dictionary, though determined primarily on the basis of the internal structure of Ẹdo, do however generally convey the broad meanings conventionally associated with these labels in their use by linguists. Thus an item identified as a noun would normally be expected to have a substantive rather than a relational reference, just as one identified as a verb would be adjudged to describe an action, state or process. However, the characteristics of some of the major grammatical categories in the language deserve further specification.

1. Nouns: These are generally substantives and they all begin with

a vowel. They usually function as subjects or objects (direct and indirect)

of sentences. Representative examples include: okpia —

2. Verbs: These generally designate actions, state events, or processes,

and they occur as the core or nucleus of the predicate in sentences. All Ẹdo

verbs begin with consonants and may be mono or multi-syllabic, though

most basic, underived verbs are monosyllabic. Most stative verbs in Ẹdo

correspond to the category of descriptive or qualifying adjectives in English.

Representative examples of words in this category are: dẹ —

3. Adjectives: These generally designate qualities of substantives.

They are predominantly ideophonic in form, and with the exception of the

few underived forms such as dan —

| 1. | wẹnrẹn | — | nẹwẹnrẹn | — | ||

| 2. | kherhe | — | nekherhe | — | ||

| 3. | mose | — | nemosee | — |

4. Adverbs: These generally modify verbs or the entire sentence or clause in which they occur. Like adjectives, they are mainly ideophonic in form and the majority are derived, usually from verbs. Indeed most derived adverbs have formally identical adjectival counterparts, and their identification as adverbs usually has to be determined from the contexts in which they occur; for example: gbadaa [gbádáá] in the sentences below can be both an adverb and an adjective, as in 1 and 2 respectively below:

The alphabetical order of entries is as shown below:

| adj. | — | adjective | ||

| adv. | — | adverb | ||

| art. | — | article | ||

| aux. | — | auxilliary | ||

| cf. | — | reference to | ||

| compltz. | — | complementizer | ||

| conj. | — | conjunction | ||

| cop. | — | copula | ||

| dem. | — | demonstrative | ||

| dem. pron. | — | demonstrative pronoun | ||

| dem. pronom. | — | demonstrative pronominal | ||

| e.g. | — | for example | ||

| Eng. | — | English | ||

| ind. det. | — | indefinite determiner | ||

| int. | — | interjection | ||

| inter phr. | — | interrogative phrase | ||

| inter. pron. | — | interrogative pronoun | ||

| inter. quant. | — | interrogative quantifier | ||

| iter. | — | iterative | ||

| lit. | — | literal or literally |

| n. | — | noun | ||

| neg. | — | negative | ||

| num. | — | numeral | ||

| obj. | — | object | ||

| part. | — | particle | ||

| pl. | — | plural | ||

| Port. | — | Portuguese | ||

| poss. | — | possessive | ||

| prep. | — | preposition | ||

| pron. | — | pronoun | ||

| quant. | — | quantifier | ||

| rel. pron. | — | relative pronoun | ||

| sgl. | — | singular | ||

| temp. | — | temperature | ||

| tense/asp. part. | — | tense/aspect particle | ||

| vb. | — | verb | ||

| vbl. part. | — | verbal particle |

| 1. | Bosah, S. I. 1976: Groundwork of the History and Culture of Onitsha. |

| 2. | Egharevba, J. U. (Chief), 1954: The Origin of Benin. Benin City. Eghareuba, J. U. (Chief), 1956 Benin Title Benin City |

| 3. | Elugbe, B. 1973: A Comparative Ẹdo Phonology. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis submitted to the University of Ibadan. |

| Elugbe, B. 1979: | |

| 4. | Greenberg, Joseph H. 1966: The Languages of Africa. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. |

| 5. | Hoffmann, C. 1974: |

| 6. | Melzian, Hans., 1937: A Concise Dictionary of the Bini Language of Southern Nigeria., London Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. |

| 7. | Moore, William. A. 1970: History of Itsekiri, Frank cass and Co., Ltd. |

| 8. | Obuke, O. 1975: A History of Aviara Madison, U.S.A. |

| 9. | Thomas, Northcote W. 1910: Anthropological Report on the Edo-Speaking peoples. London 2 Vols. |

| 10. | Westermann, Dietrich and M. A. Bryan, 1952: Languages of West Africa. O.U.P. for International African Institute. |